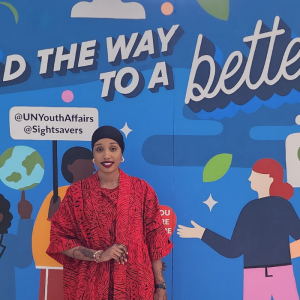

I was born and raised in Africa, so both culture and tradition are dear to my heart. I’ve always taken pride in admiring the rich cultural wealth that expands the continent and have found endless excuses to celebrate my own African identity.

However, I do believe that not all we rejoice in is worth celebrating.

Female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C), is a long standing tradition that continues to violate the reproductive health and sexual rights of women and girls throughout Africa and worldwide. Although I am a survivor of FGM/C I cannot remember how the procedure was performed or what it entailed. What I do know is that my clitoris and labia minora are absent. When I questioned my mother she told me I was cut as a six month old baby.

In attempt to justify her actions she often refers to the common saying:

‘To cleanse you in order to be accepted in society and to protect your virginity’.

What unsettles me most is that she uses religion to justify the practice. To this day I struggle to comprehend her argument because I believe that God created us to be perfect.

‘I wish I was SOLIMA’

Solima is a traditional term used to refer to an uncut woman. In some societies this phrase holds extremely offensive connotations, but in my current work in the Gambia I use it as a campaign slogan in attempt to make people think about the true meaning of the word. I forgave my mother a long time ago for cutting me. She should not be blamed for the perpetuation of the practice as she didn’t understand the negative repercussions, instead she truly believed that she was protecting me. I can never thank her enough for seeing me through all of life’s hurdles, never deserting me – not even for a second.

However, from a young age I was persistent in voicing my views against the practice, making it clear to my family that campaigning to end FGM/C is what I am destined to pursue, with the utmost commitment and dedication.

As always, it was my mother who stood strong by my side encouraging my work to promote and protect the human rights of women and girls. Her unwavering support has not always come easy, over the years she has struggled to witness the new generation of girls, especially those in her bloodline, remain uncut, but she has supported their statuses and soothed their cries at being called ‘Solima‘.

I am attempting to demystify the misconceptions surrounding FGM/C, but witnessing your community hold onto a tradition you have worked so hard to diffuse can be a serious setback. It is important to remember that this is a challenging journey, but I am always optimistic that the future looks bright.

I ha ve traveled the length and breadth of the Gambia over the years to help change perceptions and attitudes towards FGM/C and there have been tremendous achievements, but a lot still needs to be done.

ve traveled the length and breadth of the Gambia over the years to help change perceptions and attitudes towards FGM/C and there have been tremendous achievements, but a lot still needs to be done.

Every 6th February we celebrate Zero Tolerance Day to end FGM/C which measures our universal progress in ending the practice, highlighting what still needs to be done.

With the emergence of a new law against the practice, enacted in December 2015, now is the time for activists to amplify our efforts in reaching out to communities because the Gambia is far from declaring itself an FGM/C free country.

Just days after the law’s enactment devastating news of girls being cut in community back yards made my heart heavy. However we cannot let this news defeat us; it only makes us stronger and more committed to our global goal of ending FGM/C worldwide. In order to end the practice we need collective commitment from all stakeholders to help people understand the negative consequences of the practice and that FGM/C can never be justified.