This week’s announcement that G7 finance and development ministers meeting in Whistler, Canada will address key barriers to the rights and empowerment of adolescent girls is an important and welcome advancement. Also important is the fact that Violence Against Women and Girls is on the agenda at the 44th G7 Leaders’ Summit in Quebec on 7th and 8th June.

This week’s announcement that G7 finance and development ministers meeting in Whistler, Canada will address key barriers to the rights and empowerment of adolescent girls is an important and welcome advancement. Also important is the fact that Violence Against Women and Girls is on the agenda at the 44th G7 Leaders’ Summit in Quebec on 7th and 8th June.

In a heartening statement seen by Orchid Project, female genital cutting (FGC) was specifically acknowledged as a social norm that perpetuates gender inequalities alongside other types of sexual and gender-based violence which hinder adolescent girls from achieving their potential.

While FGC is a key barrier to the empowerment and inclusion of adolescent girls, as well as all women and girls impacted by the practice, it is still an underrepresented issue that must be given greater prominence within global priorities to address gender inequalities, alongside a catalogue of other sexual and gender-based violence that is linked with and/or results from FGC such as child, early and forced marriage.

At Orchid Project, we will be pushing for the importance of ending FGC to be recognised by G7 ministers, and reflected in the agreement on the Whistler Declaration on Empowerment and Inclusion of Adolescent Girls in Sustainable Development.

Here is what G7 Ministers convening on how to advance adolescent girls’ rights in the coming weeks need to know about FGC:

A global and time sensitive problem

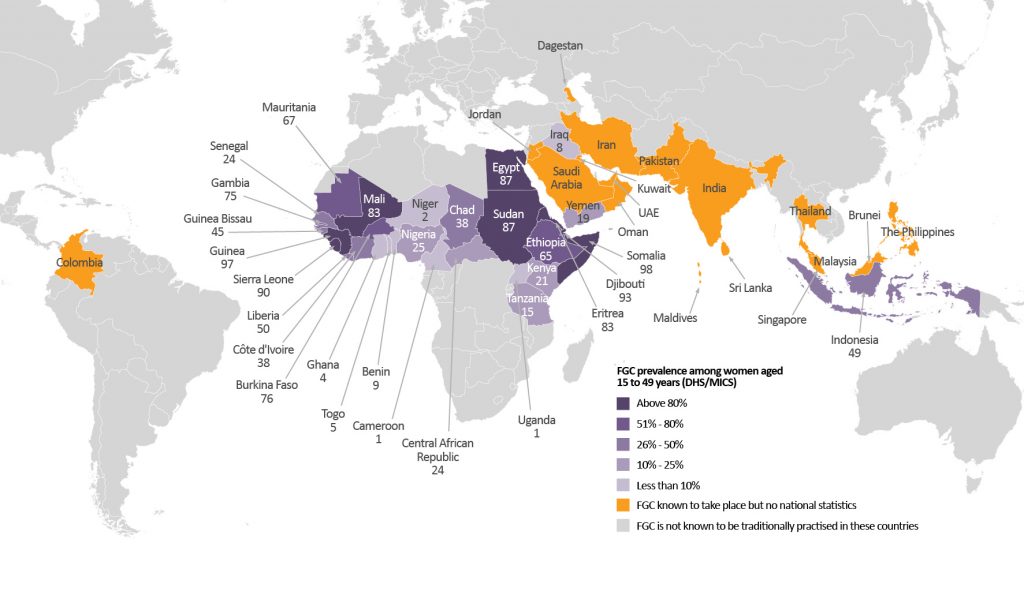

Female genital cutting is the forcible removal of a girl’s external genitals. At least 200 million women worldwide are living with the impacts of FGC, a human rights violation and often devastating form of violence against girls and women. Their health, wellbeing and access to education and economic opportunities are severely undermined by the perpetuation of the practice.

- Every year an additional 3.9 million girls are at risk of being cut. In half of the countries that practice FGC, the majority of girls are cut before their fifth birthday.[1]

- FGC contravenes human, health, child and women’s rights.

- There can be severe negative impacts when a girl is cut, including death at the time of the cut or from infection, inability to pass urine or menstrual blood, constant pain, post-traumatic stress disorder, difficult sexual intercourse and extreme obstetric complications.

- UNICEF statistics are for 30 countries: 27 countries in Africa, as well as Indonesia, Yemen and Iraq. Evidence also shows the practice in a further 15 countries, as well as in the global diaspora.

- Population growth – almost every country where FGC occurs is in the bottom quintile of the HDI; in most cases, they are also countries with the highest projected birth rate over the next decade: “The global movement to end FGM/C is at a critical juncture. If current demographic trends continue, it is likely that the absolute number of girls and women undergoing FGM/C will rise significantly over the next 15 years as populations grow, despite falling rates of FGM/C in many countries.” [2] The time to act is now, to avert this issue.

The impact of FGC on adolescent girls

FGC can have numerous negative impacts throughout a woman’s lifetime. Adolescent girls who have undergone FGC (overwhelmingly before the age of 5 in most practicing countries) experience significant additional barriers to education, access to opportunities and empowerment as a result of being cut. In addition to the acute and chronic physical and psychological impacts, the following issues are also at stake:

- Perinatal, neonatal and maternal mortality – FGC increases the risk of pregnancy complications such as prolonged or obstructed labour and post-partum haemorrhage. These are particularly likely in early pregnancy.[3]

- Child, Early and Forced Marriage – FGC is often practiced as a precursor to child, early and forced marriage, as it is often believed that FGC will ensure a girl’s purity and readiness for marriage.

- Education – there can be increased school absence and drop out due to the physical and psychological health impacts of FGC, particularly with the onset of menstruation. As a result, FGC significantly inhibits girls in reaching their full potential and limits their agency.

- Economic empowerment – impacts of FGC on education also hinder a woman’s opportunity for economic empowerment, as a lack of qualifications may prevent her from accessing employment. The ongoing health complications may result in frequent absence or an inability to work. FGC thus exacerbates economic vulnerability and can be detrimental to food security and resilience.

- Humanitarian situations – Girls and women will be particularly affected by a lack of health infrastructure if they are living with the negative health consequences of FGC. Furthermore, cut women who suffer extreme violence, such as rape, during conflict also face significant physical and psychological trauma.

Why it is essential to invest in ending FGC now

FGC is ending in thousands of communities in practicing countries, thanks to a variety of effective approaches tackling the social norm of FGC holistically. Inclusive, respectful and community-driven approaches supported by decision-makers and influencers at all levels are delivering results.

- Given the scale and impacts of the practice, FGC is a severely under-resourced issue, as recognised by DFID among many others: “However funding remains vastly insufficient to achieve the challenging and long-term change that is required. Lack of funding threatens to undermine the hard-earned gains of previous years…”[4]. An increase in resourcing to FGC abandonment programmes will ensure the health and wellbeing of millions of women and girls globally.

- FGC must be integrated and mainstreamed into all child and adolescent health, as well as education and other relevant cross-cutting programmes. It must be considered within all relevant programmes operating in a geographic region where there is a high prevalence of FGC.

- Political championship and ownership within civil society must be maintained. The Sustainable Development Goals, specifically target 5.3, offer a key framework to support engagement with the issue and abandonment of FGC. There is a UN General Assembly Resolution ratified in 2012.

Orchid Project is encouraged and hopeful for G7 ministers to discuss how the global community can take positive action together to sustainably end FGC through a holistic approach; a goal which we, together with our grassroots partners and other organisations in the sector, believe is possible by 2030.