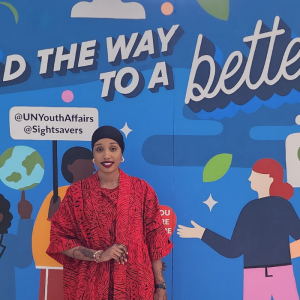

On 15th May 2014 I picked up a copy of the Evening Standard as an afterthought, to read on my commute home from St Paul’s in central London after a very informative day at a marketing event. As I descended down the escalator, newspaper in hand, my eyes captured a small image on the front cover that seemed familiar. Without paying much attention, I opened the paper to see a double page spread with the screaming heading ‘Don’t call me mutilated’ and there I was, pictured and staring back! That was the day my personal story was shared with millions, here in the UK and around the globe. It was also the very first time in my life when that I felt my voice had been heard.

Every time I think of that moment I laugh and cringe at the same time. I laugh because it was quite a memorable scenario; me trying to navigate through London at rush hour, dodging the countless glances being shot in my direction from fellow commuters, who I assumed were reading my story. So, I did what any self-respecting fashion conscious woman would – I put on my sunglasses, whilst I was on the underground. Now can you see why I laugh?

The seriousness of my story is obviously no laughing matter. Being violated, having your human rights taken away, being hurt by people that are meant to love and protect you is no joke. Feeling ashamed of your experience, hating yourself and your body is no joke. But every single day there is a girl, a woman, who has their human rights violated by the action of female genital cutting also known as female genital mutilation, or what I have termed as Forced Body Alteration – an event or undertaking that alters a person’s body without consent.

Some may say that by choosing not to use the original term female genital mutilation I am down grading the seriousness of a barbaric practice and undermining a 30 year campaign to eradicate it. The term female genital mutilation was actually coined by the Woman’s International Network founder and feminist Fran Hosken in The Hosken Report: Genital and Sexual Mutilation of Females (1979). At the time the term ‘mutilation’ was rejected and criticised as being judgemental and racist towards African woman, even medical professionals disapproved.

In my opinion, the word ‘mutilation’ used in reference to FGM is a degrading and disempowering term that strips women of their dignity and self-worth. Basically, it is a label that has the power to negatively influence ones self-identity. If you understand labelling theory you will understand how damaging/influential a term or classification can be to an individual. It is a shame that based on the use of this terminology a movement that was created to eradicate a practice has potentially discriminated and isolated more people than it originally intended.

Having just about survived my ordeal of forced body alteration I was very aware of the violation to my body. However, the introduction of the term ‘mutilation’ into my consciousness affected me mentally and physically. It made me view myself as an ugly, mutilated, and frowned upon member of society. There started my journey of self-hate, which presented itself in many forms including bulimia and social anxiety to name but a few. To be called the ‘mutilated’ girl by health professionals striped me of any dignity and covered me in shame on numerous occasions. Thankfully, I no longer see myself as a victim or survivor of ‘FGM’ – I refuse to allow that term to take away my power or to define who I am.

‘Don’t call me mutilated’ was an expression that I had previously only silently screamed to myself, and suddenly it was there for the world to see, the headline over my story. I was initially very surprised by people’s reactions and overwhelmed by the positive responses that resulted. I realised that my opinion gave people food for thought, a moment to reflect on the importance and power of the labels given and the impact of this. As well as, most importantly, raised awareness of FGC and how to better support those living with it.

Putting an end to harmful practices against girls and women should be the easiest thing to do. The fact is FGM/C or forced body alteration is an act of sexual violence and a violation of one’s human rights, which is proven to be one of the hardest and most challenging things to end. Thirty one years ago in 1985 female genital mutilation or cutting (FGM/C) was made illegal in the UK and eighteen years later in 2003 it became illegal to take a young girl out of the UK to undergo FGM/C. In 2016 the law has been amended, policies and safeguarding guidelines have been put in place, hundreds of articles have been published and documentaries produced to inform, prevent and raise awareness of FGM/C.

A lot has been done. However, the challenge remains the same now as it did over twenty years ago, around the time that I was cut – how to prevent an estimated 24,000 young girls under the age of 15 in the UK from undergoing FGM/C this year and how to provide support to those who need it. International Day for the Abandonment of FGC as a joint global action programme has gained commitment from many organisations from around the world to end FGM/C by 2030. I look forward to a day when FGC is no longer a topic of concern for young women and girls everywhere.

—

Jay K. Frederick is the founder of SKiM a platform with the manifesto to inspire, empower and emancipate those that have experienced sexual violence from labels, stigma and negative self- beliefs which will launch in the summer of 2016, for more information email hello@skimnetwork.com or tweet @jaykfrederick

Read Jay’s original article in the Evening Standard here, and to find out more watch this.