I was seven when I underwent ‘khatna’. But it wasn’t until much later in life that I understood what that meant.

When I think of it now, I can only recall fragments of the actual event; my younger sister having it done to her, the party that we had afterwards to celebrate. It was sometime into my high-school and college education that I came to learn the name of the procedure.

Female Genital Mutilation.

It sounded wrong to me. Surely, I couldn’t have undergone that.

I started researching female genital mutilation (FGM) online and was overwhelmed by the search results. I read stories about women who had been ‘infibulated’, others who had undergone ‘excision’, and women who had experienced a ‘clitordectomy’ involving partial or total removal of the clitoris and/or the prepuce. This last term seemed most familiar, a practice I can now identify as Type 1 FGM. I believed this is what had happened to me.

I needed to know more. Why and what exactly had I experienced?

I finally received answers upon a visit to my college gynaecologist. I remember watching the expression on her face freeze in shock as I explained that as a child I had undergone ‘khatna’. I was curious as to whether she could identify any difference by looking down below.

She couldn’t. Whatever had been done had healed.

I left her office feeling fortunate that I had only undergone Type I FGM. Yet, the look on her face, the utter disbelief at the words that came out of my mouth, haunted me. I recall never wanting to be looked at like that again, never wanting to be viewed as a victim. I remember thinking that I shouldn’t talk to health professionals again.

The question of “why?” remained unanswered, motivating me to pursue a qualitative research study for my Master of Social Work. It was entitled, “Understanding the Continuation of Female Genital Cutting (FGC) in the United States.” In the preceding years, I learned that FGC was practiced for many reasons, namely hygiene, sexual control, and religion. I also came to realise that FGM was illegal in the United States.

Having been born and raised in the U.S., I couldn’t fathom why my parents, why my religious community – Dawoodi Bohra, would continue a secret practice, especially one that was criminalised by federal law.

My Masters research helped develop a deeper understanding of why the practice is performed, and the complexities that surround its perpetuation. Over time I began to favour the term ‘female genital cutting’ (FGC), as an acknowledgement that this form of gender violence was complicated with culture. I realised that whatever the “justification” for the practice, the underlying reason was tradition, one I determined a bad tradition.

From then on, I wanted to do more. The world needed to know that the practice was happening here in the U.S, it wasn’t just isolated to developing countries, not just an “African” issue as has been so misconceived.

FGC is a global phenomenon, but this has only just come to light. The UN showed recent support – under Global Goal 5:3 the target and indicator relevant to FGC were changed to encourage all countries to measure prevalence rates of the practice. And just last month Unicef released new statistics recognising the true scale and impact of FGC in Indonesia stating that 51% of women and girls are affected, increasing worldwide statistics to 200 million.

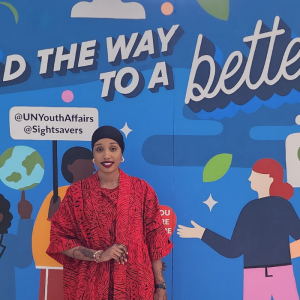

I knew I had to put my voice to this movement. I connected with women who were against ‘khatna’ or FGC and who shared my ambition of working at the grassroots to end this practice within the Dawoodi Bohra religious community.

I wrote an article about my experience for the Imagining Equality Project inspiring both Aarefa Johari, a journalist who spoke passionately on FGC, and Priya Gowami, a film-maker who had recently completed “A Pinch of Skin” – a documentary on ‘khatna’ amongst the Dawoodi Bohras in India to connect with me. Our initial exchange sparked an immediate connection, together we reached out to Insia Dariwala, a documentarian and Shaheeda Tavawalla, a researcher, and as we conversed on the topic that united us all we realised we had created a space for change. We were compelled to broaden the conservation, and so began to lay the foundations for an organisation facilitating just that.

Sahiyo was born in 2015. The name translates as the Bohra Gujarati word for ‘saheliyo’, or friends, and reflects our organisation’s mission to engage in dialogue with the community to find a collective solution towards ending the practice of FGC or ‘khatna’. As an organisation we are dedicated to empowering Dawoodi Bohra and other Asian communities to end FGC and create positive social change. By working towards an FGC-free world, we aim to recognise and emphasise the values of consent and a child’s/woman’s right over her own body. We aim to enable a culture in which female sexuality is not feared or suppressed but embraced as normal.

Sahiyo was born in 2015. The name translates as the Bohra Gujarati word for ‘saheliyo’, or friends, and reflects our organisation’s mission to engage in dialogue with the community to find a collective solution towards ending the practice of FGC or ‘khatna’. As an organisation we are dedicated to empowering Dawoodi Bohra and other Asian communities to end FGC and create positive social change. By working towards an FGC-free world, we aim to recognise and emphasise the values of consent and a child’s/woman’s right over her own body. We aim to enable a culture in which female sexuality is not feared or suppressed but embraced as normal.

As a first initiative Sahiyo launched an online survey on the extent of FGC amongst the Dawoodi Bohra community globally – we are excited to release the findings in May. Most recently, Sahiyo started the Each One Reach One campaign in collaboration with Speak Out on FGM, a month long campaign encouraging Dawoodi Bohras to break the silence on ‘khatna’ and talk to one another. In the future, Sahiyo will be conducting an extensive field survey in India on the extent of FGC, making more documentaries on the practice, holding community workshops, and gathering more stories from survivors.

We know that FGC won’t end overnight, but there is momentum in the air – FGC has been acknowledged as a global issue, one affecting women and girls worldwide. Help us break the silence. Join the conversation on FGC at #EachOneReachOne or connect with us at sahiyo.com or sahiyo2016@gmail.com.